Exploring the Modes of the Harmonic Minor: Part II

And MORE versions of "Happy Birthday" you'd wish you hadn't heard.

Introduction

Welcome back!

In the previous instalment, we explored the harmonic minor and its first two offspring: the tense-but-interesting Locrian♮6, and the oddly cheerful yet slightly sinister Ionian♯5. Along the way, we discovered how a simple tune like “Happy Birthday” can be warped into something quite unfamiliar—and a little unsettling—by transposing it using these altered modes.

This time, we’re diving into the final four modes of the harmonic minor family. Some of these are surprisingly usable, while others are, well, you’ll see.

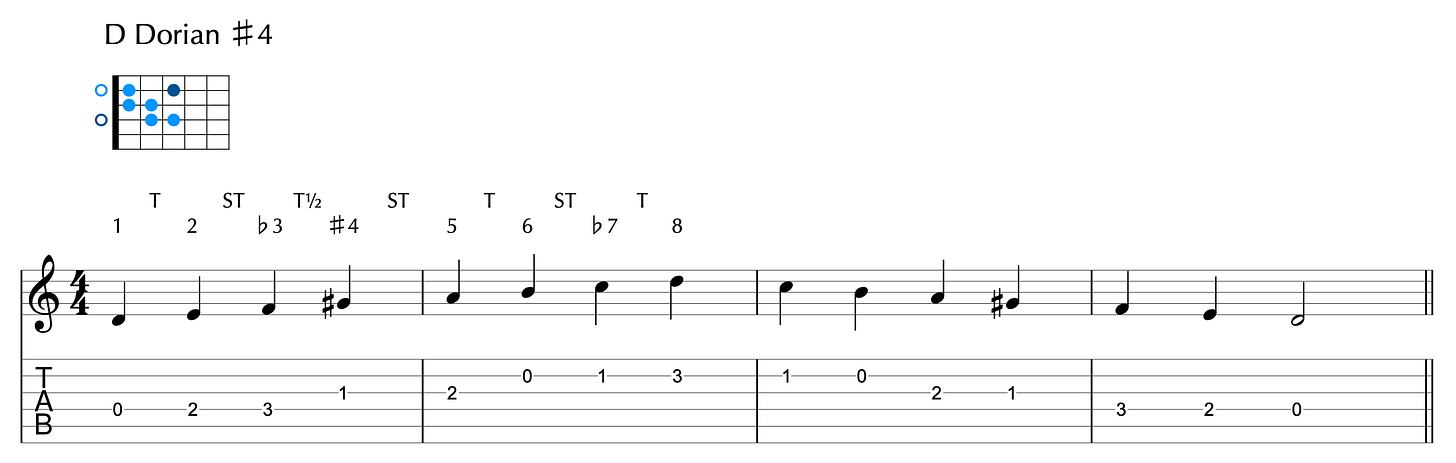

Dorian ♯4

Let’s pick up where we left off with something that’s actually useful.

This mode goes by a few other names—most commonly Ukrainian Dorian or Romanian Dorian. Despite those labels, it appears widely in traditional music from across Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Balkans. It’s especially common in folk, klezmer, and Romani music, and was a favourite source of inspiration for classical composers like Bartók and Kodály.

What makes Dorian ♯4 so compelling is its tonal ambiguity. Like the Dorian mode, it has the raised sixth that gives it a slighter brighter minor sound—but the raised fourth disrupts expectations, bringing a tinge of major-mode brightness, albeit briefly. It hovers in a kind of modal limbo: brighter than the natural minor, but too unstable to sound truly major. This major/minor identity crisis gives the scale an expressive, almost restless quality.

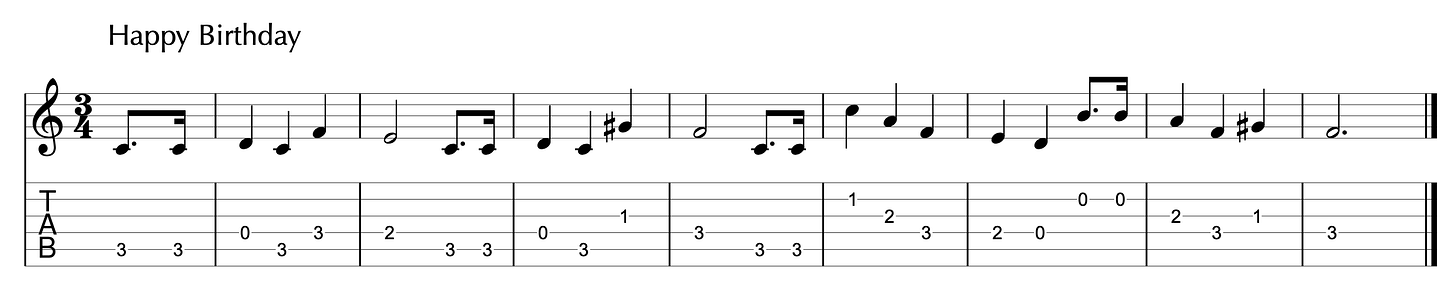

Here’s “Happy Birthday” transposed into D Dorian ♯4.

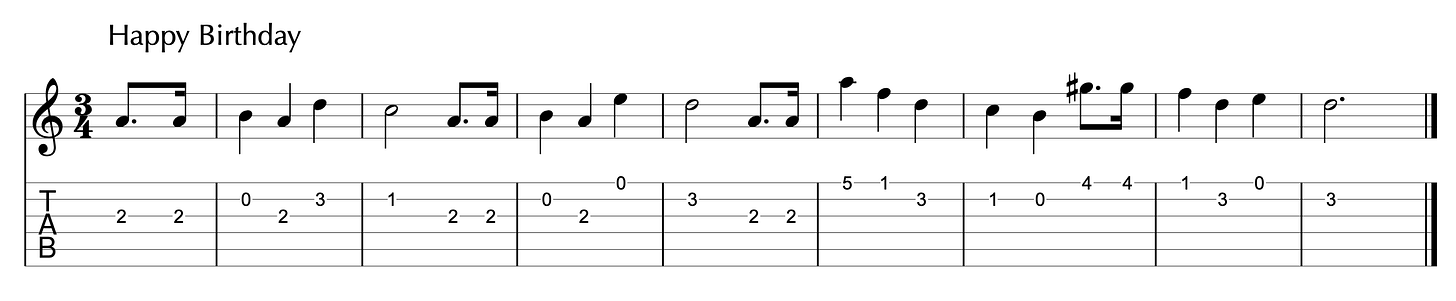

Phrygian Dominant

Our fifth mode is the Phrygian dominant.

Among the harmonic minor modes, this one is probably the most widely used. It’s very close to the Phrygian mode, but with one crucial difference: the third scale degree is now a major third above the tonic, instead of a minor third. You now get an augmented second between the second and third degrees (F to G♯), which gives the scale its exotic, unmistakably Middle Eastern flavour.

This mode is often used to suggest Arabic, Jewish, or flamenco musical styles, and its dramatic sound makes it a favourite in everything from film scores to metal solos. It’s also about to do some very strange things to “Happy Birthday.”

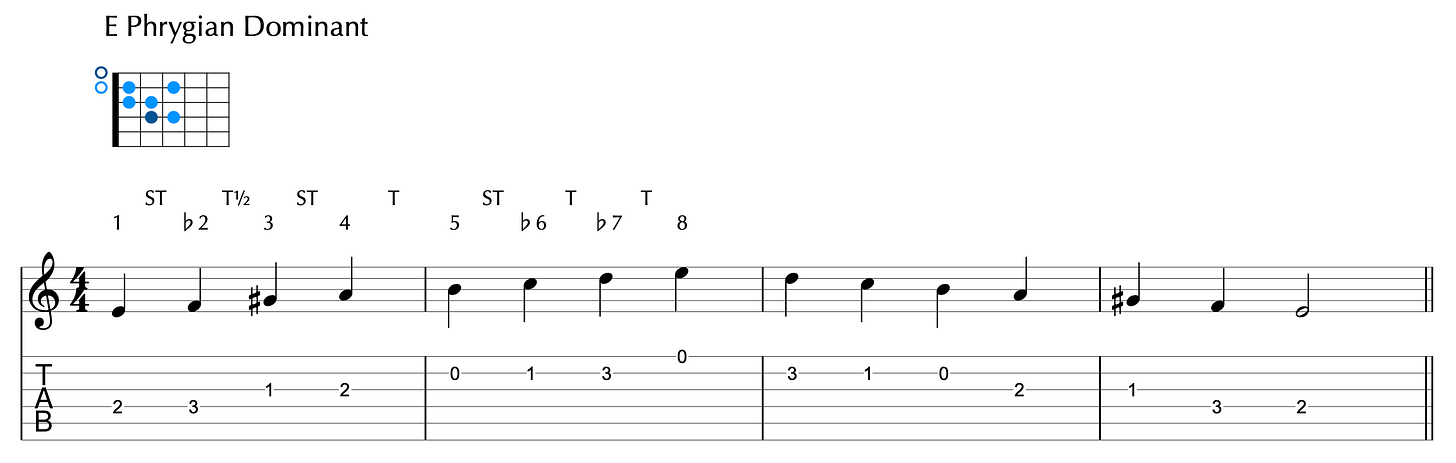

Lydian ♯2

Just like the Lydian—but with more sharp.

The location of the augmented second interval (F to G♯) gives us a raised second degree in addition to the Lydian’s raised fourth. This immediately makes the scale sound a little off-kilter. Though, harmonically, it gets even stranger. The tonic chord is still a major triad (F–A–C in F Lydian ♯2), but if you enharmonically reinterpret that raised second (G♯) as A♭, you suddenly also have the notes of the tonic minor chord (F–A♭–C). In other words, the scale implies both major and minor tonality at once—a strange duality indeed.

That awkward augmented second step creates a kind of lurching return to the tonic—one you’ll definitely hear in the version of “Happy Birthday” below. You’ve been warned.

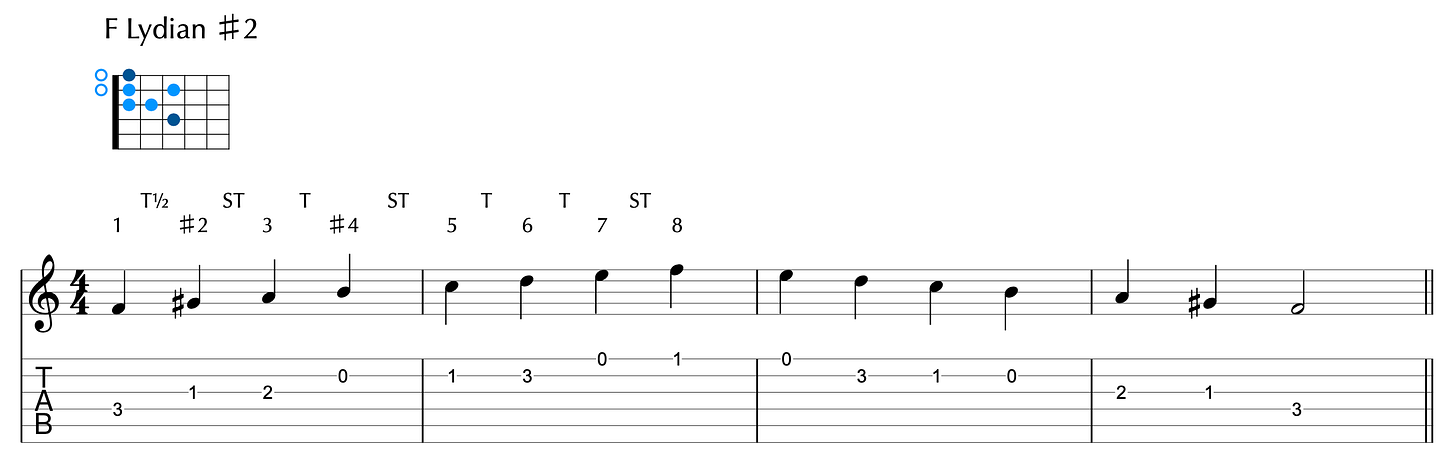

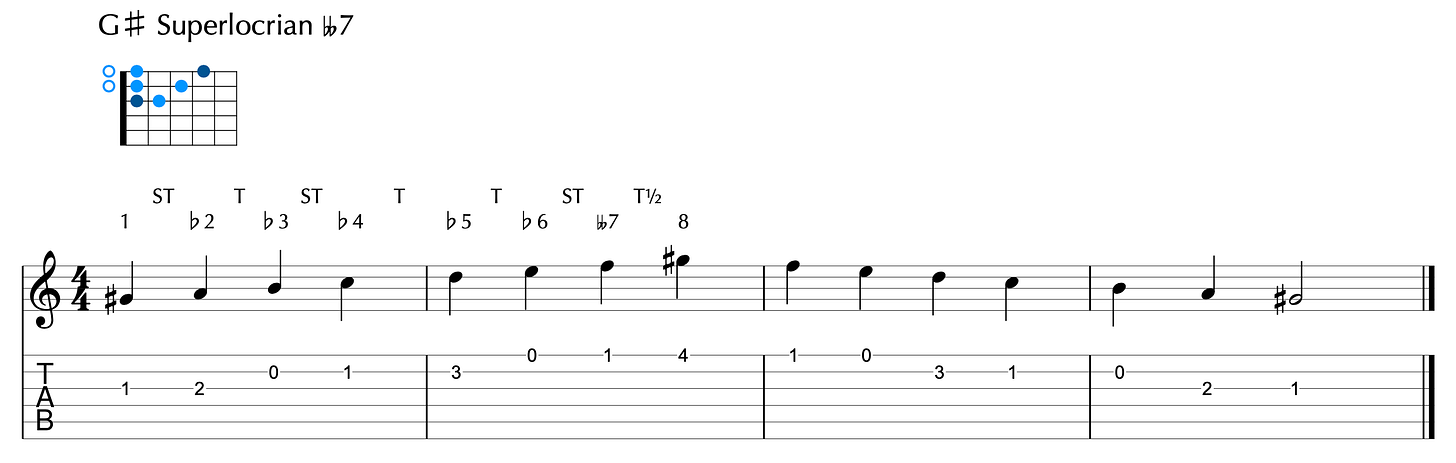

Superlocrian 𝄫7

Not just your regular Locrian.

Wait—haven’t we already had a Locrian? Yes—but this scale is a variant of the G# Locrian mode, which is the seventh mode of A Major (and the parallel major of A minor). The Superlocrian 𝄫7 retains all the characteristics of your usual Locrian mode, with two extras: a lowered fourth and the already flattened seventh flattened again. In this case, G becomes G𝄫, which is enharmonically the same as F.

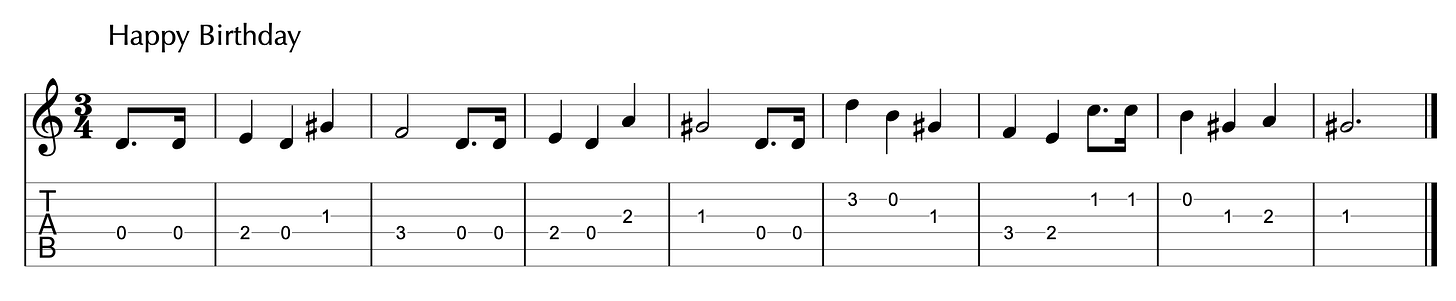

The result is a scale that’s barely holding itself together—it’s so unstable it’s hard to harmonise in any conventional way. Melodically, it’s tense, jagged, and restless. Still, there’s something strangely fascinating about hearing such a familiar tune warped through this final, most altered of altered modes. Here’s “Happy Birthday” in G Superlocrian 𝄫7. Try not to look directly at it.

It’s Over!

And there you have it—the seven modes of the harmonic minor, each putting its own weird and wonderful spin on the world’s most innocent melody. From the folkish charm of Dorian ♯4 to the full-blown chaos of Superlocrian 𝄫7, we’ve seen how a simple change in scale can completely transform musical character. Some of these modes are harmonically rich and evocative; others are downright unhinged. But each one opens a window into the expressive possibilities of modal thinking. So next time you find yourself stuck in a musical rut, maybe try modally manipulating your tunes—you might just find something interesting!

Catch you in the next one.

~R